We got out before it got too bad, but still it was like hell come to earth at times down in the mines. Wish I had never heard of coal mining, but how you gonna earn a living in Kentucky if you ain’t got no education, no training, no nothing? A job is better than none, Mama always said, and she wasn’t wrong about that.

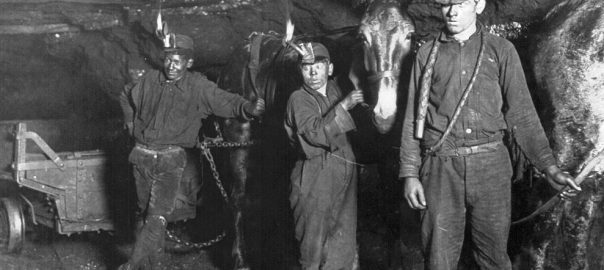

Started when I was only 15 even though it wasn’t legal. The company would look the other way if you had kinfolk who were already working for them. Since Daddy and Uncle Jack had been down in the mines for years, they let me go with them and work the Danderoff vein until it was picked clean. Took us months just to get to the best part of the mine, dig out that coal and send it down the line. End of the day you’d be coughing your damn fool head off, but it was good honest work and it was better than starving to death.

‡ ‡ ‡

It was sometime in May, a week before Mother’s Day when the explosion happened. Said later it was a buildup of methane gas deep inside the guts of the mine. I was just going in for the day, was standing at the entrance to the mine and suiting up for the day’s work when the world started to tremble under my feet. Felt like I was being shaken loose from my skin and bones. I hit the ground and started praying, asking God to protect me. I wasn’t thinking of anyone but myself for that moment, just praying God would let me live.

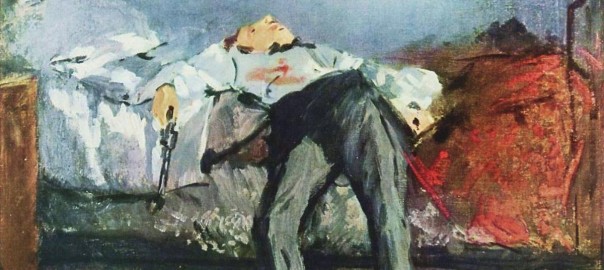

Took them nearly a week to clear a path so they could get to the dead miners. Found 57 bodies and buried them in pine boxes the company deducted the cost of from their salary before they turned it over to their wives. Never knew how damned I was until that day. It hit me that one day that was gonna be me. One day they’d be telling some girl I had married that I was dead and gone, buried under tons of rock. So I got out when I could and moved away.

‡ ‡ ‡

Since then, life’s been anything but easy. I was homeless for a few months at first, then managed to hook up with a construction crew just outside Mobile, Alabama. Worked with a sledgehammer and road tar for years before my back gave out.

Along the way I got married three times and had four kids. Three sons and a daughter who died when she was only a year old. Had some rare blood disease they said might have been passed down on my side of the family. Nearly drove me crazy when she passed, but I got by with some help from liquor and tears mixed together. Seems like I can’t even manage to do the job of Dad right.

Now I live alone here in the mountains of West Virginia. I don’t have much, but I do have some peace and quiet most days. My sons all work in the mines now, and I wish I could help them get outta that life, but it’s not possible. I just hope and pray one day they’ll do better than I did. I tried to be a good man, but I failed more than I met the mark. Guess it doesn’t matter since Dr. Baker says the lung cancer should finish me off before the year’s out.

Not long ago some kid from the college down in Morgantown came to talk to me and said it was for some paper he was writing for a class. He wanted to know what I’d learned in my years. And I thought a long time before I answered him and said, “Nothing, really. Not a damn thing. Nope.”

Later, the kid sent me a copy of the paper he wrote, but I didn’t read it because I know good and damn well how it ends.

Copyright 2016 by Andrew Bradford. All rights belong to the author and material may not be copied without the author’s express permission.